This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Faust

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Faust

Performance in three parts

Translated by Leonas Švedas

Opening took place in Lithuanian National Drama Theatre in Vilnius on October 26, 2006.

Duration of the performance: 4 hours

Produced by Meno FortasTheatre

Co – produced by

Emilia Romagna Teatro

Theatre de la Place, Liege

Theatre – Festival „Baltic House“ St. Petersburg

Lithuanian National Theatre

Aldo Miguel Grompone

with the support of Lithuanian Ministry of Culture

Director Eimuntas Nekrošius

Stage designer Marius Nekoršius

Costume designer Nadežda Gultiajeva

Composer Faustas Latėnas

Light designer Džiugas Vakrinas

Cast

Faust Vladas Bagdonas

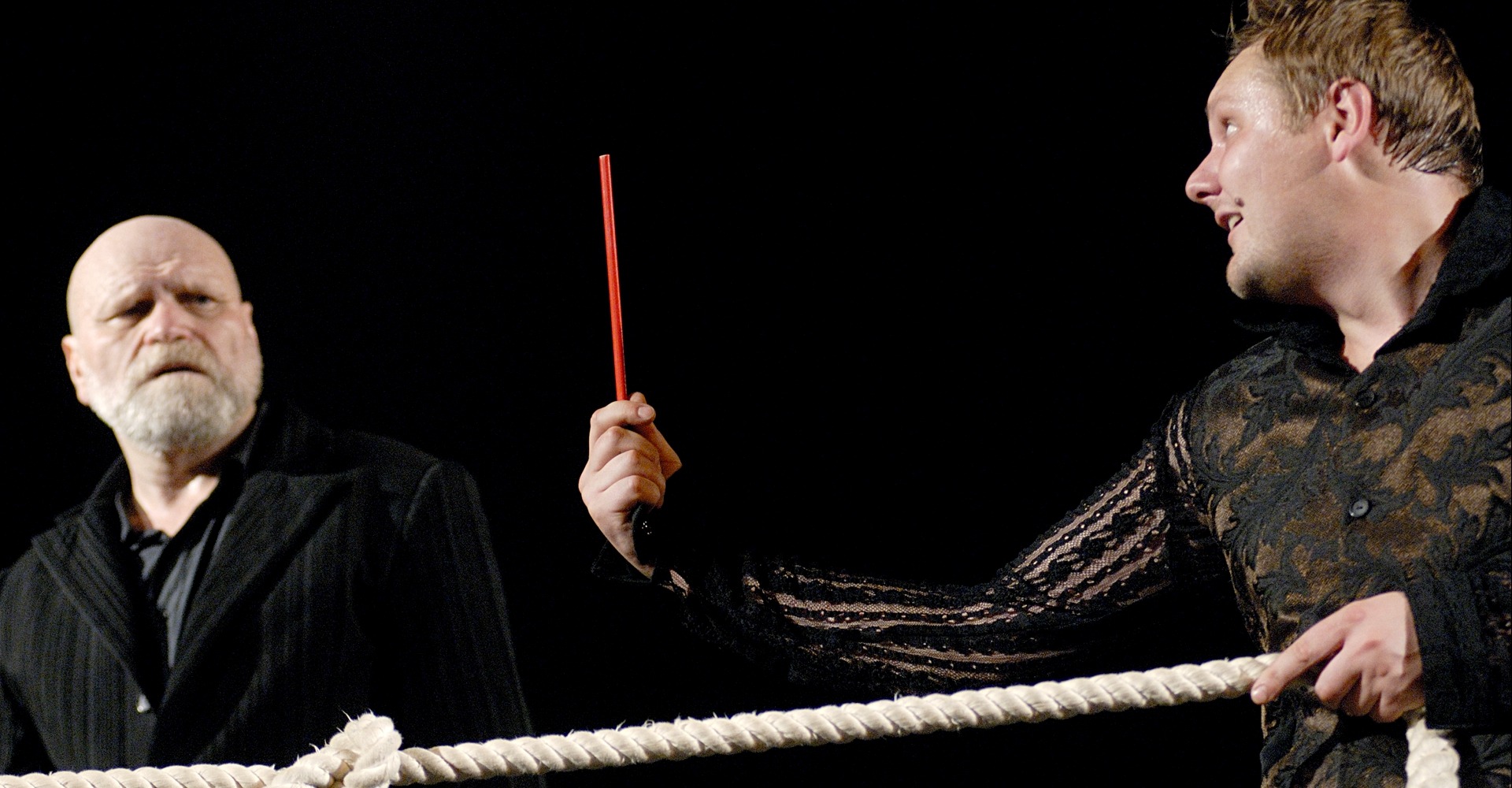

Mephistopheles Salvijus Trepulis

Margarita (Gretchen) Elžbieta Latėnaitė

God, Wagner Povilas Budrys

Spirit, The dog Vaidas Vilius

Valentin Kęstutis Jakštas

Spirits

Diana Gancevskaitė

Gabrielia Kuodytė

Viktorija Streiča

Margarita Žiemelytė

Vladimiras Dorondovas

Viačeslav Lukjanov

Director‘s assistant Tauras Čižas

Sound designer Arvydas Dūkšta

Prop man Genadij Virkovskij, Vladimir Frolov

Technical coordinator Džiugas Vakrinas

Faust’s Mystery Play

“Faust” by Eimuntas Nekrošius

[…]

In my opinion, Nekrošius’ “Faust” is closer to what Goethe said about his own works, “It is the marrow of my bones and the body of my body”. In fact, the performance is closer to the director’s body and seems to be breathing with his spirit. This is best reflected in the Dedication of “Faust”, which does not sound in the performance, but as if floats in the air and permeates the image of Faust with the mood of longing. Faust is an eternal traveller with a soul torn in two: he is both longing to experience the wholeness of nature and condemned to loneliness. The motif of journey is probably the key image in the performance. It connects the symbols amply scattered in its three parts and seems to reveal the secret of Faust’s condemnation as a man and a creator: he will keep wandering as long as he is alive. As long as, like in the performance, God keeps turning the lever of the beam like the axis of the universe, patiently and evenly, and Mephistopheles keeps casually aiming at the heavenly bodies zooming around with a self-made rifle…

The first scene of the performance, the Prologue in Heaven, is not only the quintessence of action, but also the model of this stable state of things, which both renders “Faust” earthly and simple and elevates it to symbolic heights. In this scene one can discern the first layers of the performance: the undivided unity of good and evil, heaven and hell, firmness and fragility, which is in fact only the changing cycles of creation and destruction, appearance and disappearance. As if everything were made by human hands, as if man himself, wiping off the sweat, turned the earth.

[…]

It is not so difficult to find in Goethe’s “Faust” the sentences or metaphors that have been turned into graphic, spacious and emotionally suggestive images of the first two parts of the performance. A more important thing is that while marking the trajectory of the word and thought towards action, these sentences sound as an expression of a searching, suffering and creating soul, calling for the spirits’ help to clear away the darkness of ignorance and impasse. It is not by accident that in this kind of “Faust”, parallel narrative lines, concrete settings or the rejuvenating drink is not needed. Faust longs to experience “nature” while staying what he is. Maybe that is why he meets Mephistopheles as if having waited for him for a long time, and sees Margarita-Gretchen the way he was dreaming of her; the performance is so constructed that having been preparing himself for the agreement-signature for such a long time and having sought Satan’s help with all his body and soul, Faust enjoys the new experience only for a moment – touched by Gretchen’s madness.

On the other hand, the director does not spare tenderness and an understanding ironic smile for Faust’s restless soul. Faust invokes the spirit of Earth (Activity), and here comes a little man waving a big flag and laughing in Faust’s face. […] It seems that however much vanity Faust may have, Mephistopheles and his servant mocks and parodies it – they turn Faust’s expectations upside down and transform his contrived concepts and categories into simple material shapes. One would say that they enjoy his suffering, so that before long they could show him what pain, loneliness and loss is all about.

Rasa Vasinauskaitė, “Faust’s Mystery Play. Faust by Eimuntas Nekrošius”, 7 meno dienos No. 734, 2006

In the Beginning Was, Will Be, Let It Be…

[…]

It would be difficult to imagine that having decided to produce “Faust”, Eimuntas Nekrošius would deal with heaven and hell, reality and illusion in the manner suggested by Goethe. Exhilarated and sweating, the Lord (Povilas Budrys) is turning the Sun and the Earth with all its oceans, granites and thunders. He is tangibly, sensuously real with every movement of his muscles. Movement, work and the mover himself are as real as the tool of moving – a self-made wooden pole, convenient for the hand and shoulder. Therefore that what is being turned in this manner at that moment does not have even a theatrical reality, let alone some “more serious” one. The sun, the earth or granite is not to be found in this physically concrete “here and now” – great matters are not born from the materiality of a stage object. It is a clear visual metaphor, which more or less helps to build the relations between the dramaturgical and the directing text and helps the consciousness of the perceivers of the performance to form a network of associations, to catch meanings and to reveal other dimensions of the performance. […]

“Faust’s” characters are signs of the bodily memory of the mankind. The philosopher, theologian, physician and magician himself bears several marks that cannot be erased by any kind of experience – his arms put out in front of him draw a hieroglyph of futility of knowledge, darkness of education and existential fallacies. His arm turned up towards himself signifies a collection of scientific instruments, – a monumentally frozen frame, with each movement as if forcefully dragging his body through space. This figure created by Vladas Bagdonas could remind us of his Othello, but Faust’s sculptural character is full of inner elemental force and real power. Faust’s body looks like an empty abstraction because he has discarded any relation with the earth. It is not by accident that the scene of producing and drinking the youth elixir is absent in the performance, and a glass of water that he has drunk fills Faust with something opposite to his not-yet-exhausted powers.

In the meantime, Margarita-Gretchen embodies another paradox. Her movements consisting of organic but more abstract lines draw a broken, fragile, sharp and agile figure on the threshold of her not only feminine, but also human essence. The actress almost perfectly creates a Margarita who still has a lot of “pre-humanity”: she is extremely sensuous and “touches” the world with her clairvoyant instincts – smelling, biting and gnawing her lover’s nails.

The meeting of Margarita and Faust, though tainted with a rather bitter irony, could not end otherwise but tragically. The essence of the tragedy lies deeper than words and ideas, it was given along with one’s body from the very beginning. Love here is drawn only in a contour line, like death; only the latter is drawn in another colour.

The director draws a clumsy, apparently formless Mephistopheles with equally fine brushes, though in less “important” colours; a white shining line devoid of any décor marks the Lord, and an elaborate shaky Wagner played by Povilas Budrys is drawn by a laughing hand. Black ink and several strokes of a poster brush are used to draw a group of spirits, crows, rats and citizens. Several horizontal lines on the stage mark the cardiogram-hell-sea, as well as a web of an electric bulb of “knowledge”, niggling as a fly. The graphics of tree branches are executed in softer strokes. A conical city covered with bronze foil…

Vlada Kalpokaitė, “In the Beginning Was, Will Be, Let It Be…”, Literatūra ir menas No. 3121, 2006